In the early 2000s, Matt Damon was busy making a name for himself, built off of the momentum of his career from the 90s, which included netting an Oscar for Best Screenplay for his work with Ben Affleck on Good Will Hunting. Essentially, Damon had his pick of roles. After this win, two of his most famous roles were the lead in The Talented Mr. Ripley and a significant player in the ensemble action-comedy-heist Oceans Eleven. However, when people talk about Matt Damon, there is one role that surpasses them all, and that is Jason Bourne.

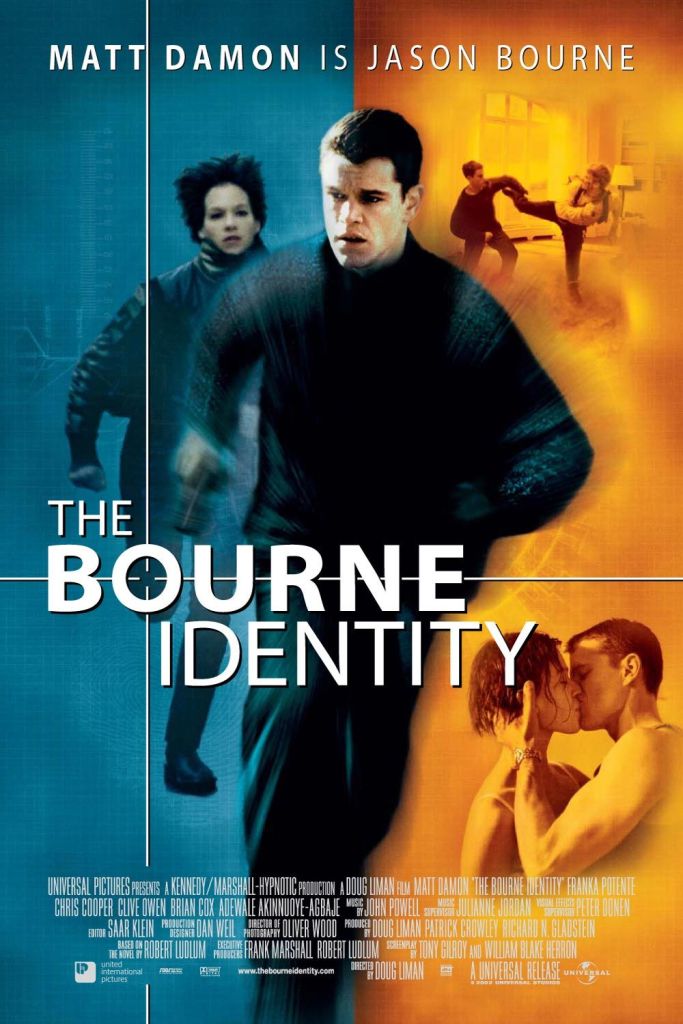

First introduced on the silver screen in 2002 with The Bourne Identity, the story’s basic premise follows an amnesiac young man struggling to figure out who he is and what he has done with his entire life. It’s a blank slate, but fragments of his previous life haunt him, and with them have come skills and abilities he has no conscious knowledge of how to wield. However, practicing something long enough and devoting enough attention to it becomes secondhand and reflexive. Whoever this man was, he was a capable combatant and multilingual. A couple of fishermen yank him out of the Mediterranean, and once a subdermal chip is found, he has his first clue. Everything spirals out of control from there, as they often do in conspiracy films.

At a bank in Zurich, a safety deposit box provides numerous passports, foreign currency, various credit cards, and assorted technology – all the makings of a covert agent, including a loaded gun. He takes everything except for the gun, and decides to use the name Jason Bourne from the litany of identities at his disposal. The problems arise when a figure claims to have proof that the U.S. tried to have him assassinated recently, leading the CIA to scramble in an assortment of different directions with conflicting agendas.

What separates The Bourne Identity from most of its sequels is that it is one of only two out of five (currently in existence) not directed by Paul Greengrass. As a result, it has a distinct tonal difference from all of its successors, including the Jeremy Renner-led fourth film, wherein the tone had been laid in stone two films in a row. Still, many of these differences show how the world and its characters have evolved. Of course, Jason is more open and emotive in this outing. After all, he has yet to go through all of the hell and trauma that is unleashed upon him across four films.

One of the major differences is how effective the CIA is at executing its vast operations. It certainly has numerous successes, such as completing the mission that Jason Bourne didn’t do before the film began? It also took down innumerable threats to its cover black operations programs. However, it feels as if they are all-seeing Gods in the sequels, whose successes never end and result in a plethora of dead bodies between Jason and his mission to find out who he is and expose the truth. One thing that never changes is that if they had simply left well enough alone, none of the plots would have happened. This is a central tenet of any good conspiracy film. It relies on an overly reactive, emotional response from those who are desperate to keep their illicit activities in the shadows. Who knows how far Jason Bourne would have gotten with his amnesia if they hadn’t interfered. He doesn’t remember much until the fifth film, over a decade later. Perhaps dozens of operatives and CIA leadership officials would be enjoying a nice glass of wine and a good cut of steak if they had just put on blinders like they wore when they initiated their heinous programs.

Alas, there would be no plot without an antagonistic operation that is equally competent, overzealous, incompetent, and self-destructive.

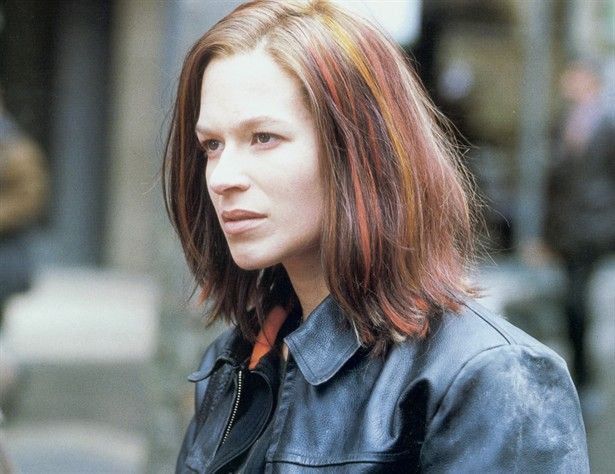

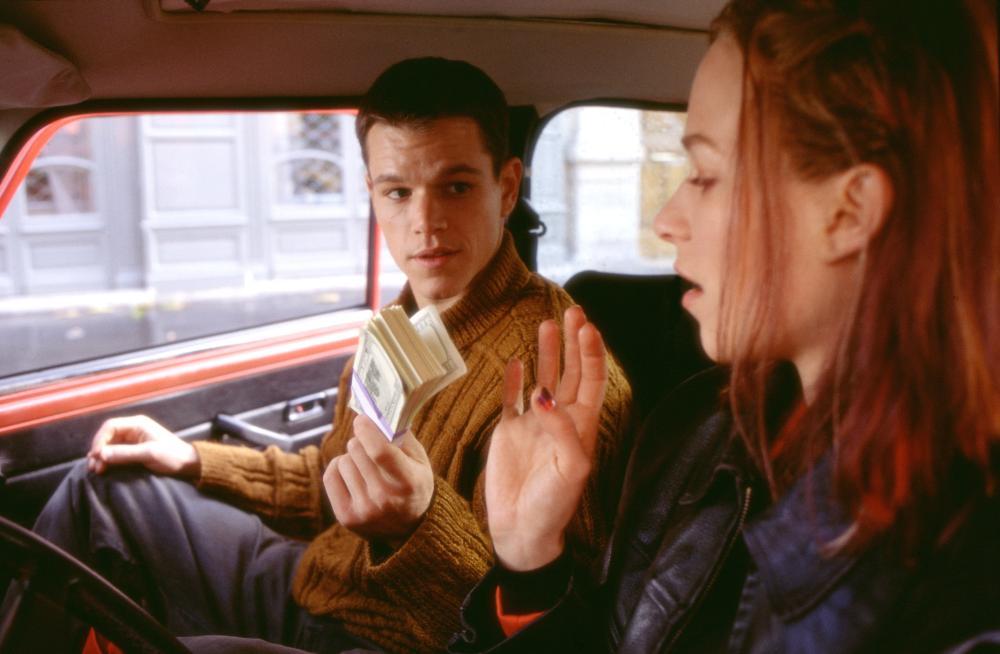

As Jason travels across Europe, trying to piece together everything he knows with the fragments he is gathering after each encounter, he meets Marie (Franka Potente), who has recently been denied a student visa.

She is a nice person, but she ends up drawn into Bourne’s circle early into the film when she unwittingly becomes his accomplice after he pays her to drive him out of town. Marie is Jason’s only ally, and she spends the vast majority of the film with him (something Rachel Weisz shares with Jeremy Renner in their movie). As a result, we get to know her quite well throughout the film. By the time they reach Eamon’s farm, late early into the third act, the pair have thrown themselves into a relationship due to the hectic, frenetic chaos from the past few days. No, it technically doesn’t qualify as Stockholm’s Syndrome. When Marie realizes Jason is a threat, the assassins after them are far more significant threats, and she is no longer safe in your everyday, typical society. Her normal life is gone.

Brian Cox stars as Ward Abbott, presented as a CIA Section Chief who is the superior to Alexander Conklin (Chris Cooper), the man in charge of Treadstone. This program gave birth to Jason Bourne and a slew of others. We are introduced to several of Treadstone’s operatives throughout this entry, with three getting focused on. Castel (Nicky Naude), Manheim (Russell Levy), and the Professor (Clive Owen). Each gets their chance in the spotlight, directed by Conklin to eliminate Jason Bourne posthaste and by any means necessary. This is where the CIA’s conflicting agendas play brilliantly. Who is dispatched, when, and for what is unclear until the particular operative executes their missions. Brian Cox, however, would ultimately go on to play a much larger role in the sequel.

Several supporting players fill out the ensemble, such as Danny Zorn (Gabriel Mann), who is Conklin’s assistant and the overseer for the analysts who work in Treadstone’s control room. Nykwana Wombosi (Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje), the African dictator who was Bourne’s final target for assassination, whom he failed to dispatch and thus proves to be a thorn in Treadstone’s side for most of the film. Lastly, we have Nicky Parsons (Julia Stiles), known for her romcoms, who is a CIA field operative coordinating logistics for Treadstone. Of all of them, she is the most crucial character (though even Zorn nudged in a second appearance), despite playing a bit part in half of her appearances. Each successive appearance elaborates her connection with Jason Bourne, allowing Julia Stiles to spread her dramatic wings widely and well.

Julia Stiles took a dip into a more action-oriented world for this film, Nicky Parsons seems out of place in the world of Jason Bourne, but that’s because she is part of the base of support that it is all built upon. While their are people at the top who issue assassination orders with little remorse or care for collateral damage, it’s people like Nicky and Danny who make those orders practical and bring them into reality. Despite Hollywood magic, in a world where we are constantly under surveillance, even far less sinister than the Bourne franchise would have us in, getting weapons and gear to an operative is no easy task. Especially on short notice. Nicky exists to make this possible. Without her, programs like Treadstone would crumble under their own weight.

Ward Abbott is emblematic of all the problems that the CIA represents throughout the franchise. Like Conklin, Abbott is dedicated to covering up their crimes, which includes disposing of those who work for him that get in his way.

That anybody who knows the real man would continue supporting him is, quite simply, insane.

The film is replete with choreographed fight scenes, thrilling car chases, and fast-paced stunts that boggle the mind. From the surprisingly sudden attack by Castel when Jason and Marie are at his apartment, picking through his sparse life for clues to the police chasing down Bourne through Paris, resulting in untold damage and casualties as he effectively evades them, the film ramps up the tension and the thrills. Events never go how we expect, such as Castel’s decision after their fight ends in Jason’s favor to Manheim’s actual target near the film’s conclusion. This is why it seems as if there are too many cooks in the kitchen at the CIA regarding Treadstone. Each entry only builds off this, further muddying the waters as one more conspiracy is thrown over the others to try and stave off exposure.

The Bourne Identity lays the groundwork for everything that comes next. Its vast web of conspiracies continues to unfold, revealing the metastasized corruption that flows through the veins and arteries of the United States government. The film is adapted from Robert Ludlum’s Cold War-era novel. Thus, several significant changes were made to the plot and its characters. As one of the most recognizable franchises, this continues to prove the exception to the rule that pragmatic adaptations are a bad thing. Based solely on the main throughline for the original novel, the film would necessitate being a period piece and focus on far lower stakes than the adaptations ever did. Both are good entities, and obviously, the film would not exist without the book, so perhaps it’s time we focus on enjoying media for its respective strengths.