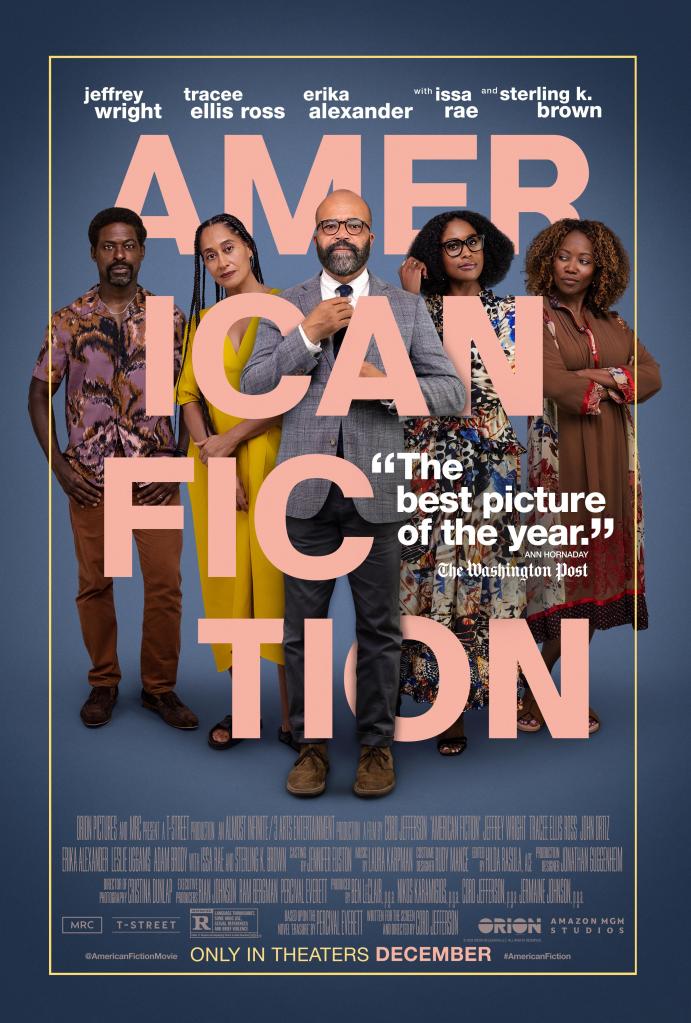

Last year, American Fiction came out to ask a series of questions. Chief among them, what is black literature? How does the black experience relate to the overall American experience? How impactful is “family” in the black community? Are the hollow stereotypes truly what drives commercial success for media centered on blackness?

Alright, I’ll be honest; these were questions that I derived from American Fiction. But audiences around the country engaged with this film to different degrees – as is the norm. Yet, American Fiction was unafraid to be critical and introspective at every level.

Based on the novel Erasure by Percival Everett, director Cord Jefferson worked closely with Everett regarding the changes that would be made to translate the story from book to film. As is often the case, changes frequently occur for any number of reasons – one of the chief changes is how the text of My Pafology/Fuck is handled. Erasure literally includes the entire text of the book, and while American Fiction clocks in at nearly two hours, there is not nearly enough time to devote to the entirety of a book. Let alone two, when you include We’s Lives in Da Ghetto by Sintara Golden. Yet, the film takes time to engage with the book and its impact on the world in which it takes place, and it provides keen insight when necessary.

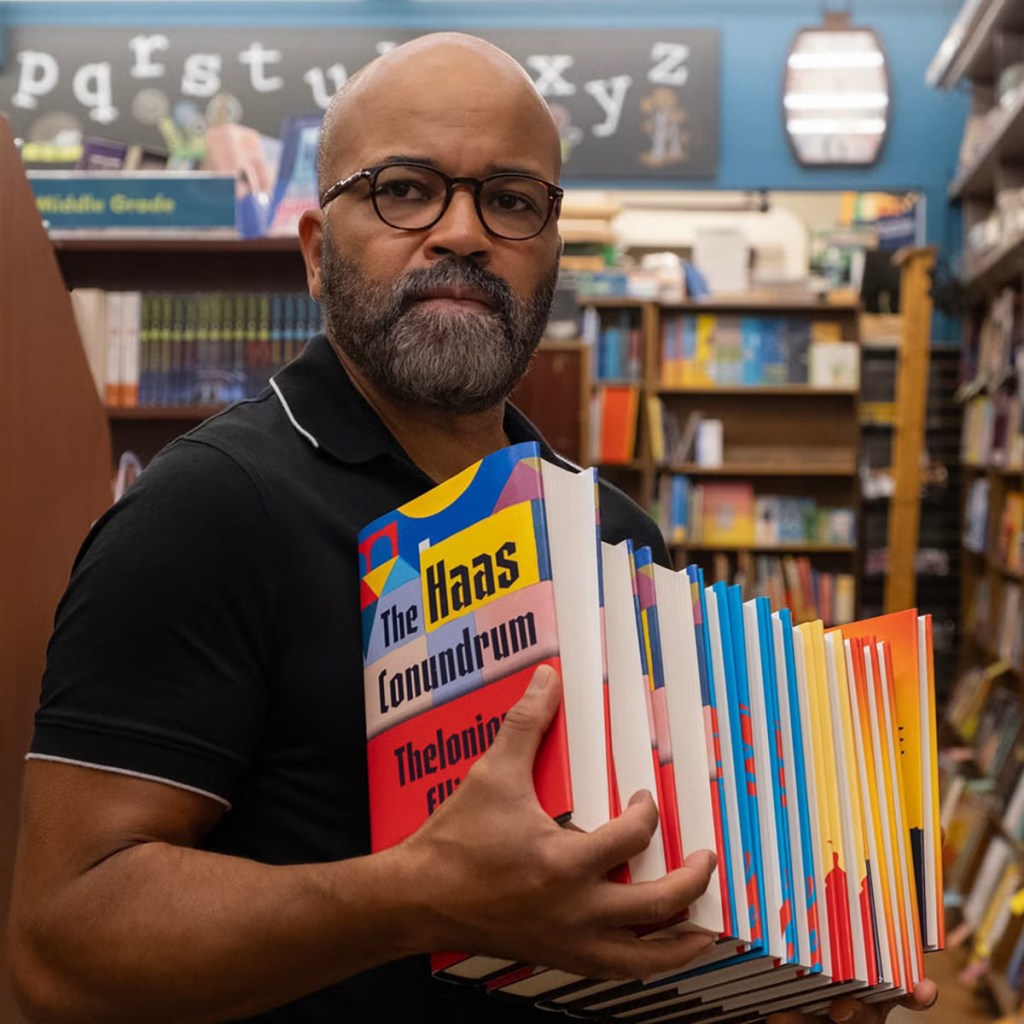

American Fiction centers on Dr. Thelonious “Monk” Ellison (Jeffrey Wright), a writer and professor of literature whose work is often based on metafictional reinterpretations of Greek tragedies – works nobody reads. His publisher has been pushing him to write more “black” centered books, which frustrates Monk because that isn’t the kind of literature he wants to write.

One scene is entirely devoted to his frustration that his work is relegated to the African-American section of a bookstore solely because it is written by a black man. His comments on the situation ring hollow with the white salesperson.

The major characters in the film are the people who surround Monk – his sister, Dr. Lisa Ellison (Tracee Ellis Ross), and Dr. Clifford “Cliff” Ellison play central roles at different points of the film, driving home the importance of family. Their mother, Agnes (Leslie Uggams), is suffering from Alzheimer’s and requires round-the-clock care from Lorraine (Myra Lucretia Taylor). Her diagnosis has severely impacted the Ellison children, especially Lisa, who has been forced to further balance her time with taking care of her mother, her job at a major hospital in Boston, and the apparent apathy from her brothers towards the situation. When Lisa and Monk reconnect, they are busy preparing for their mother’s impending death, bringing us to the film’s first major twist. Cliff, who is gay and is more interested in cocaine, provides a clear contrast to Monk, who is merely checked out of the more significant issues surrounding his family.

Lorraine is not merely relegated to the background. She begins a romantic relationship with Maynard (Raymond Anthony Thomas), a security guard in the area where the Ellisons’ beach house is located. She is a caretaker, but it is clear that she is also a powerful presence in the Ellisons’ lives. Somebody they trust and love.

The supporting cast also circles around Monk to varying degrees; Arthur (John Ortiz) is Monk’s agent, who has been striving to help him get his next book through. The only problem is that nobody wants the work Monk is writing because it doesn’t delve into the topics they want from a black author. Coraline (Erika Alexander) is introduced as Agnes’ neighbor. She’s a public defender and begins a romantic relationship with Monk throughout the film. Next is Sintara Golden (Issa Rae), whose book has already started making the rounds throughout the literary circuit, gathering attention and increasing Monk’s frustration because of its subject matter. Sintara’s book delves deeply into a particular kind of black experience, focused on drugs, and crime. While it is undoubtedly sensational, its presence acts as a lightning rod for commentary. Its existence is thematically relevant even if only excerpts are all we get.

Paula Baderman (Miriam Shor) and John Bosco (Michael Cyril Creighton) are two publishers seeking to publish My Pafology. Early in the film, an argument erupts between Monk and one of his students, who exhibits the kind of performative “justice” that is often on our minds. She argues that Monk shouldn’t use the N-word because it makes her uncomfortable, and his caustic response leads to him being put on temporary leave. His work is not selling, his family is in shambles, and the sight of Sintara’s packed seminar, compared to his lackluster one, prompts him to write My Pafology, later titled Fuck. The work is derivative of everything that Monk hates but what the market clearly craves: melodrama, broken families, gang violence, and drugs. His shock at their offer of $750,000 as an advance and his building personal and financial crises drive him to accept – under the name Stagg R. Leigh. Everything begins to unravel from there, as even a major movie producer, Wiley Valdespino (Adam Brody), is interested in taking Fuck to the next level. Wiley’s involvement takes everything much further, and the impact that Fuck has begins to spread wider and further than Monk can control.

While his career as a writer is the impetus for most of the film, American Fiction is a quiet drama focused on Monk’s life. That is where the film’s strength lies. It entirely contextualizes the critiques within the film as an indictment of how the film will be treated. American Fiction is not a film focusing on the black experience. Yes, the entire main cast is black, and yes, it is about their lived experience and how the greater world treats them as people despite their upper-class lifestyle, but that’s the point. American Fiction is centered on the “American” experience, and the main cast just happens to be black. A central question is, “Why is the lived experience of a people boiled down to their skin color rather than the society in which they live?” Monk and his family could be entirely exchanged with people who were white, and only minor differences would be included.

As a drama, the characters’ relationships often drive the story forward. How they interact with one another, and their conflicting viewpoints provide a necessary balancing act to the rest of the plot – which is centered on Fuck. How the characters react to the book’s existence is just as important as their individual relationships with one another.

American Fiction, like most quiet drama films centered on family, is meant to evoke just that. Black Americans go through the same experiences as all Americans do. They must contend with the rigors of balancing work and home life, neither willing to slow down to accommodate the other. Monk’s family is left in flux when tragedy strikes, and he must grow and evolve to fill the shoes that his sister left behind. Yet, he quickly realizes the invisible work crushing his sister’s shoulders when the power goes out in his mother’s house. Because he forgot to pay the bills.

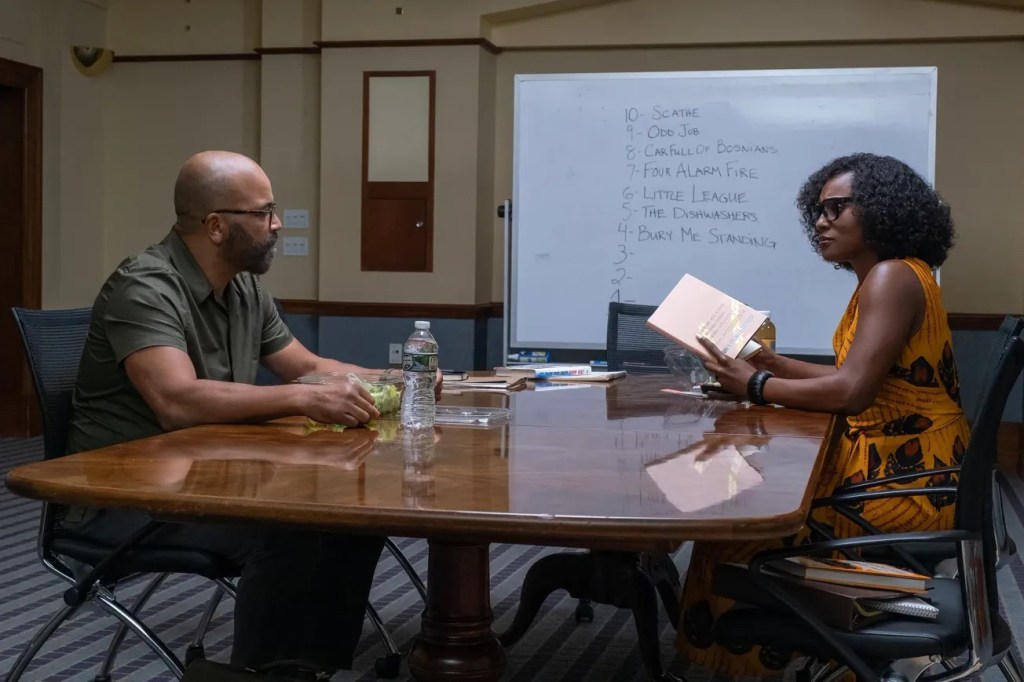

Near the end, we come to two of my favorite scenes – a debate between five characters and a conversation between Sintara Golden and Monk, specifically comparing Fuck and We’s Lives in Da Ghetto. At this time, only a handful of people actually know that Monk wrote Fuck, and Sintara is not one of them. They’re two of five writers serving on a panel that is set to award a literary award, and Fuck has simply captivated the country. The panel’s other members are two white men and a white woman – Jon Daniel Sigmarsen (Bates Wilder), Wilson Harnet (Neal Lerner), and Ailene (Jenn Harris). Because the organization had almost no diversity, Sintara and Monk were asked to be on the panel by Carl Brunt (J.C. MacKenzie). By the time Fuck is making the rounds and gaining traction, the panel is ecstatic to include it in its list of options (with Monk’s objections ignored).

The debate between the panel involves the three white people lamenting that they aren’t listening to black voices and unironically overrule Sintara and Monk when the pair challenge Fuck’s inclusion on the list, let alone to be the winning choice. This scene is used to, with the subtly of a hammer on porcelain, show that even when white people are attempting to be empathetic and engaged with black work, they can miss the mark if their intentions are not pure. Countless authors of color release books every year that doesn’t rely on the kinds of stereotypes that Sintara and Monk utilized in their work, and they are often ignored in favor of more sensationalist works like their two books. In an attempt to elevate the voices of black authors, the panel very noticeably ignored the voices of two black authors in the room.

Next is the discussion between Sintara and Monk – where we learn that Monk’s frustrations with Sintara’s book are based on a rather dangerously incomplete understanding of her book. Because he hadn’t actually read it.

This scene is intentionally left ambiguous. You can walk away with the knowledge that Sintara wrote her book for much the same reason that Monk wrote Fuck – for the money. Yet, as the two go back and forth, she lays out a case for why her book is better and should be more impactful – she did research. She built her book off of a collection of anecdotes from multiple sources. She then compressed that into a compelling narrative, which is now overshadowed by a work she views as “pandering.” The major difference between the two: Sintara read Fuck before judging it, even though she fully understood what it was that she was going to be reading. She engaged with the work and then made her own decisions about its worth.

The literary world is insular, where success and failure are measured differently from other industries. 5,000 books sold will put an author on the New York Times Best Seller list. Keep in mind that if the book is priced at $24.95, this would only translate to an amount of money just shy of $125,000. American Fiction as a film earned $23 million during its theatrical run against a budget of $10 million. By that metric, Fuck is a financial disaster, and yet it’s a critical darling. American Fiction focuses on these many conversations, reaching a conclusion that truly meets the mark – even if it’s a major point that is missed by many.