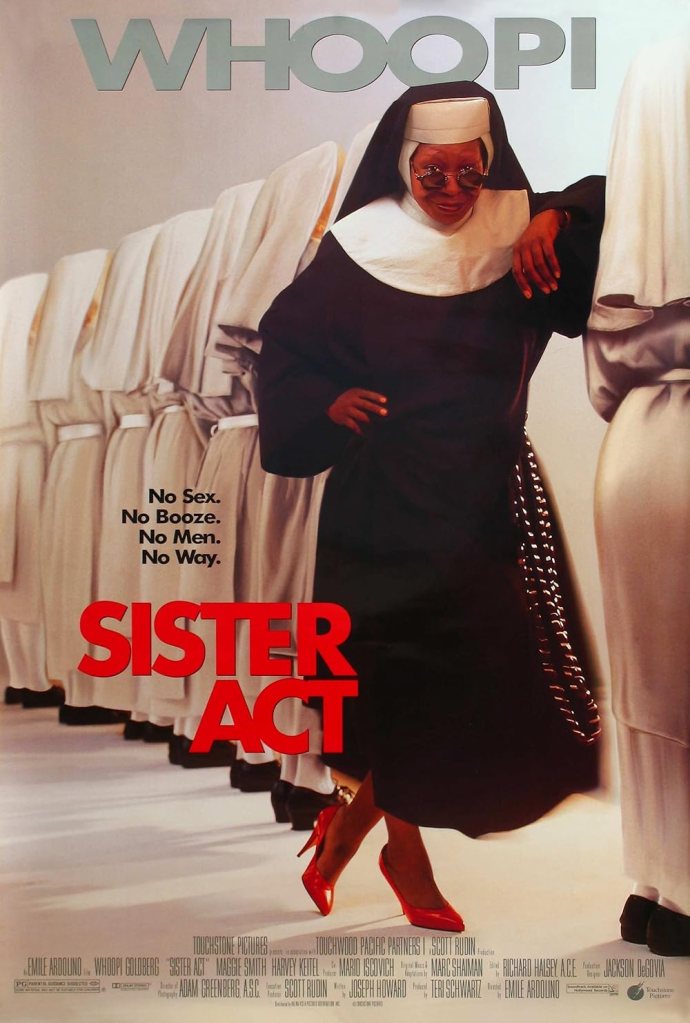

Musicals and comedies go hand in hand, kind of like peanut butter and chocolate. While Whoopi Goldberg might be on record as disliking singing personally, nobody can truly say that she is bad at it. That, on top of her comedic timing, turns Sister Act into one of the most hilarious goldmines of her long and storied career. With the grittiness of the 90s on full display, we are treated to a hilarious set of circumstances that present an intriguing take on “witness protection.”

Deloris van Cartier (Goldberg) is a Reno showgirl – ahem, lounge singer – and the mistress of a mobster, Vince LaRocca (Harvey Keitel), who has been under active investigation by the Reno PD for a long time. When he gifts her a fabulous mink coat, which just so happens to belong to his wife, Delores storms up to him only to witness him murder a witness against him. Having seen the crime with her own eyes, she flees as quickly as she can and ends up in the hands of Lieutenant Eddie Southner (Bill Nunn), who offers her protection. Because of the time it will take to get a court date, even with LaRocca in custody, Southner decides that witness protection is the safest place for her. He plants Deloris in “the last place” anybody would think to look for a Reno lounge singer, a catholic convent under the name of Sister Mary Clarence.

The film actually starts with Deloris as a child (briefly played by Isis Carmen Jones). It reveals that she attended Catholic school, which helps further explain why she bristles at this particular placement. The first portion of Sister Act, set in Saint Katherine’s Parish (based in San Francisco), is dedicated to her struggling to settle into an environment that is wholly different from what her life was like, and exceedingly more restrictive than what she would like. Ignoring her circumstances, this setting helps Deloris grow as a person without sacrificing the core of her character.

While there are men involved in the oversight of the convent, including Monsignor O’Hara (Joseph Maher), the day-to-day operations are overseen by the Reverend Mother (Maggie Smith), who is frustrated to no end by Deloris’ presence. While she is sympathetic to Deloris’ circumstances, the Reverand Mother is focused on protecting the safety and security of the women under her charge in an environment that has changed drastically from when she was a young nun. Like Deloris, the Reverend Mother is also forced to grow as a person, and she, too, doesn’t give up her central tenets as a person when she does. Deloris and the Reverend Mother act as foils to one another, forced into the same space with vastly different priorities. Still, it is the Reverend Mother’s insistence that Deloris fit in with the convent to prevent the other nuns from being aware of why she is here that leads to the main plot.

Deloris is naturally a wonderful singer, so it makes sense that, considering she cannot execute the other tasks the nuns have been taught to do flawlessly, the Reverend Mother would place her in an environment that best suited her skills. To her eternal exasperation, in less than a day, “Mary Clarence” completely overhauls the choir, resulting in the nuns taking on a decidedly more invigorating style. This change doesn’t take long to spill out into the community, slowly providing the kind of safe haven that the Reverend Mother had lamented about having long since vanished. While the Reverend Mother desperately wanted to yank Deloris out of the choir and return it to its sanctified roots, Monsignor O’Hara notes that their attendance greatly increased because of the music and overrules her.

Through the choir, most of the ensemble is fleshed out, especially when Mary Clarence begins to help them find themselves. Three of the more notable members, with character arcs woven into the main plot (though not to the same degree), are Sister Mary Robert (Wendy Makkena), Sister Mary Lazarus (Mary Wickes), and Sister Mary Patrick (Kathy Najimy). Mary Robert is the youngest sister introduced in the film, and the one who initially befriends Deloris upon her arrival. Portrayed as quiet, Deloris helps her find her voice, literally and figuratively (Mary Roberts’ singing voice was provided by Andrea Robinson). Mary Lazarus is one of the older members, who often weaves in anecdotes about “the good old days,” but is equally devoted to the choir, even if she bristles at some of the changes at first. Sister Mary Patrick, who has been misplaced in the choir, is loud, boisterous, and friendly to all, making her one of the easier friends for Deloris to make and support. Together, these three make Deloris’ time in the convent bearable and, over time, quite enjoyable.

Sister Act, as a musical, devotes much of its runtime to its musical numbers, almost all of which are religiously updated covers of very popular songs. It delivers flawless performances from the choir throughout, each one memorable enough that it is understandable why the community, the church, and ultimately the Pope himself, view this as a marked improvement worthy of recognition. Deloris uses her skills as a performer to breathe life into each performance, telling a story not just through song and dance, but through community. She weaves the church’s belief system into the music that she teaches the choir, giving it a bit of edge while never losing the foundational core of who these women are and what their mission is. That is the kind of execution that takes not just skill and effort, but a willingness to listen and adapt.

It comes at a time when reaching out to the community was far more of an imperative to the convent than the Reverend Mother wanted to admit. Because, for her, reaching out felt like a double-edged sword. As the community deteriorated into an active danger to the sisters, they could no longer bring their perspective to it without risk of threats of violence. If not for Deloris, the church’s place in the community would have continued on a downward spiral toward being closed. It makes the final act of Sister Act feel, not merely earned, but predestined.

Sister Act is one of those rare films that bridges the ‘80s and ‘90s into something that still feels timeless, even if you can accurately peg it to when it was released. Its thematic elements and central message are timeless. In a time when it feels like we couldn’t be further apart, a woman like Sister Mary Clarence is always there to remind us that there “Ain’t no mountain high enough, ain’t no valley low enough, ain’t no river wide enough,” to keep us apart if we’re not willing to let it.