Scream (1996) acted as a reminder that a slasher film could be a film first and a slasher second. Slasher films were a hallmark of the 80s, but by the 90s, they were becoming increasingly passé through the sheer formulaic execution of their stories. While it’s safe to say “depth” in a slasher film can often feel little more than a surface quality, this tends to be because audiences often don’t engage with the material meaningfully. Scream did not hesitate to do this in such a way that it felt revolutionary at the time, but prescient in the long run.

Slasher films, in general, often tackle complex social issues with more nuance than your typical drama. The thing is that these issues are couched in analogy and symbolism. That might be a problem if it weren’t for the fact that all media do this. Perhaps it’s the glut of murder that leaves the message muddled for those unwilling to put in the effort. That is to say, what Scream brought to the table wasn’t just a cast of characters to be murdered with little to no characterization; it provided a mystery that was eerie to watch unfold across its runtime.

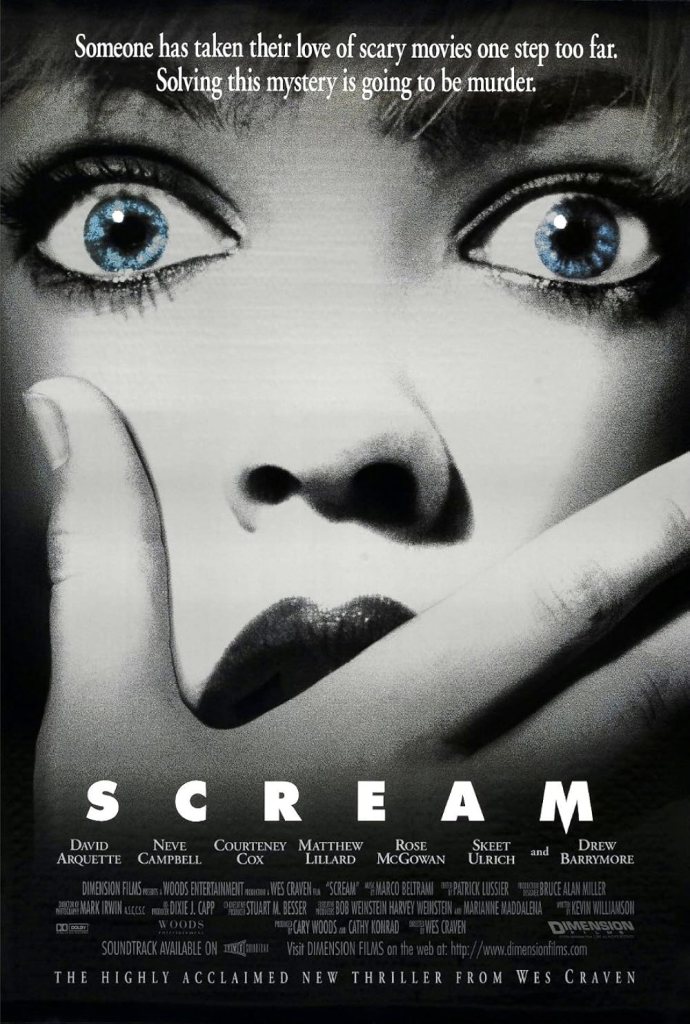

Directed by legendary horror icon Wes Craven, who crafted some of the most inventive horror films that have ever hit the silver screen, including one of the big three, Freddy Krueger. A mere two years after reinventing the character again in Wes Craven’s New Nightmare, Craven would combine forces with screenwriter Kevin Williamson, who wrote the script after he was struck by inspiration from the Gainesville Ripper. This wasn’t to glorify the murders or the killer, but all media draws from the world around us. Scream took strides to explore the sensationalism of crimes like this by baking it into the marrow of its story.

What set Scream apart from its predecessors, which were becoming increasingly derided for their tried and true storytelling techniques and stock characters who bordered on stereotypes, was its meta acknowledgement that slashers existed. It was rare for the characters in a film to acknowledge, let alone rely on, the genre conventions that they were constrained by – only for that knowledge to not be entirely helpful all the time. Because, at the end of the day, Scream was not “a movie,” but “real life” being portrayed as a movie. It treated itself as if it were really happening. Unfortunately, a well-prepared killer can get the drop on you, even if you know what to look out for.

The characters in Scream are presented in a microcosm of their lives. Each character feels like they had a life before they first appear on screen. Throughout, they’re constantly referencing past events that serve as the basis for current decisions, relying on relationships and how they reinforce or break trust amongst one another, and even withholding information from us as a secret waiting to jump out at the most inopportune moment. None of the characters feels like a character in and of themselves. They feel like a real person thrust into a traumatic event with rapid unexpectedness, turning what looks like established personality traits upside down. I have always felt like Scream mastered the question, “Who are you in the dark?” Just because a character is kind and compassionate does not mean they aren’t prepared to fight like their life depends on it. Because in Scream, it most certainly did.

Scream also did something rare in the horror genre by casting popular teen idols in its major roles. While modern audiences can point to Johnny Depp and Kevin Bacon as big stars now, the same is not true for the cast of Scream. Their appearances in A Nightmare on Elm Street and Friday the 13th were at the beginning of their careers – the acting debut of the former and the fourth film of the latter, respectively – but the likes of Neve Campbell and Drew Barrymore were household names.

Audience-goers went into Scream believing that Drew Barrymore was the star because, of course, she was. She was by far the biggest name in the movie, and the marketing went out of its way to portray her as such. By now, her opening scene is so iconic that it feels patently impossible to go into Scream without knowing that she’s the second on-screen victim (I won’t fall prey like she did).

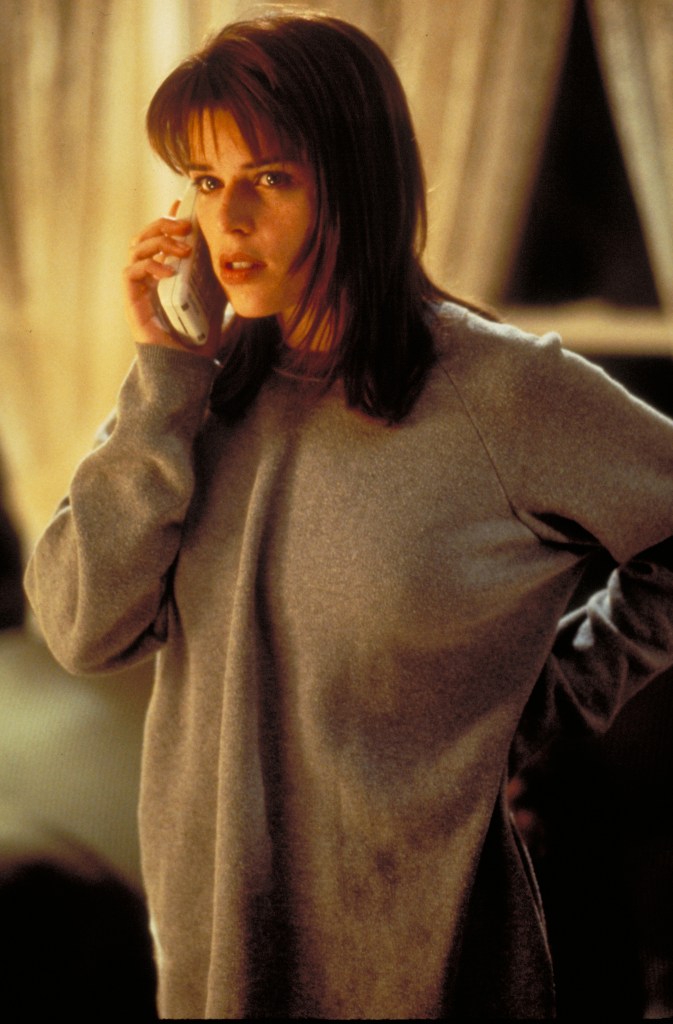

The primary cast for Scream existed as a pseudo-ensemble, centered around Sidney Prescott (Neve Campbell). After the opening, the film introduces her and her boyfriend, Billy Loomis (Skeet Ulrich), and the fact that her father, Neil (Lawrence Hecht), is going away on a business trip the following day. Her best friend, Tatum Riley (Rose McGowan), the younger sister of Woodsboro Sheriff’s Deputy Dewey Riley (David Arquette), and her boyfriend, Stu Macher (Matthew Lillard) and their mutual friend Randy Meeks (Jamie Kennedy), are all introduced shortly thereafter, as Woodsboro High School becomes a media circus amid the revelation that Casey Becker (Drew Barrymore) and her boyfriend, Steve Orth (Kevin Patrick Walls) were murdered the previous evening.

This core group of friends is the main cast and, unlike the Big Three (Friday, Nightmare, and Halloween), we are treated to a mystery regarding who is Ghostface. Although the killer would not become known as this colloquially in-universe until the fourth film, he is famously referred to as such by Tatum in her big scene. The rest of the main cast includes the iconic Gale Weathers (Courteney Cox), a reporter who is building off her big break from covering the murder of Maureen Prescott (Lynn McRee) and the subsequent trial of Cotton Weary (Liev Schreiber), the previous year. Her trusty cameraman, Kenny Jones (W. Earl Brown), is always following her, with complaints in hand, as she seeks to make history and stop a spree before it can reach its planned conclusion. Finally, we have Principal Arthur Himbry (Henry Winkler, uncredited), who was literally a cameo before the producers ordered an additional death scene to be added when it was realized that there were 30 pages of script without a death (between Casey and Tatum).

The characters did not just exist to die. They weren’t caricatures waiting in line for the plot reaper to come for them. So, regardless of how much or little their screen time was, Scream had to ensure that you knew who they were and would care about them. It made the deaths of the characters hurt because they weren’t just characters at the end of the day.

Scream did not ignore the conventions that made horror films what they were. It identified and joked about them and then proceeded to show with brutal efficiency why they exist in the first place. One such memorable point is during Sidney’s first call with Ghostface, during which she lambasts potential victims for running upstairs rather than the front door. Over the course of her call, as she becomes increasingly unsettled, Sidney engages the security chain on her front door, unaware that the killer is, and had already been, inside her home the entire time. When Ghostface bursts from the foyer closet behind her, Sidney’s initial instinct is to go for the front door. Still, there isn’t enough time to get it open, necessitating her running upstairs, because it is the fastest escape route in her panicked state.

The film sets this up beautifully because when Sidney returns home from school that day, she makes a long trek around behind her house through the back door, passes said closet while getting ready for Tatum picking her up that evening, and hears a sound from it, but ignores it. This plays with another convention: “Why don’t the characters act like a killer is around?” At this point, Sidney has no reason to believe that a killer is targeting her, no reason to behave like she is in any danger, or act like a strange sound is a reason to feel anything but mild discomfort. While we, the viewers, know the killer who stalked and murdered Casey and Steve is a masked psycho who called and taunted Casey, the rest of the characters… don’t. This is Scream’s greatest strength – it is a movie that acts as if it is real life. When we turn on the news, all manner of terrifying things are reported, but nobody suddenly acts as if a seemingly random act of violence is the prelude to a serial or spree killing. Why, then, would Sidney?

Scream provided a blueprint for the 90s and early 2000s for slasher films. Self-referential characters, a killer who could be a member of the group of core characters rather than a random stranger, and “story” with murder rather than “murder” with story. At two hours, including the credits, Scream has a total of five victims, not including Ghostface. Most slasher films tend to have seven deaths as a baseline, not including the killer, if they are even defeated. The producers made a point of adding a death because the film still needed to be a slasher film. Still, that additional death served a narrative purpose. It cleared out the house party to set the stage for the final act. The deaths did not happen because the story said so. They happened because the killers were executing a story. Each Scream film that followed is successful when it remembers that, even if they do up the body count.

With Scream 7 set to debut in a handful of weeks, proving that the franchise is resurgent once more, time will tell if those entries that follow remember the core strengths. With Kevin Williamson helming the seventh installment, I personally am looking forward to seeing how the originator of the story can execute his vision.